Introduction

For millions of Pakistan’s poorest households, social protection means the difference between survival and destitution. The IMF-backed Benazir Income Support Program (BISP), Pakistan’s flagship social protection initiative, has been hailed as a model for international aid. Yet, with poverty rates rising from 34.2% in 2022 to 39.4% in 2023 (World Bank, 2023), a troubling question arises: are these policies truly lifting people out of poverty, or merely keeping them afloat? In the development space, the IMF refers to social protection as a set of policy measures designed to improve the socioeconomic conditions of the most vulnerable households in impoverished nations (IMF, 2017). Though this conveys a commitment to inclusivity in the global economy, the tendency to rely on a Quantitative Approach (QA) in formulating the policies for social protection foregoes the impact on critical low-income beneficiary stakeholders. By assessing the IMF’s interventions in an emerging economy such as Pakistan, with a focus on the aims and outcomes of policy interventions in relation to social protection, a more complicated story emerges. By contrasting QA development with a multidimensional framework such as the Capability Approach (CA), proposed by Nobel laureate Amartya Sen and others, it becomes clear that true development must be measured not only by financial inputs but by tangible improvements in people’s freedoms and opportunities.

Pakistan’s Case: The Limits of a Quantitative Approach

Pakistan exemplifies an emerging nation grappling with low human development levels in relation to social and human capital, with nearly half the population living below the poverty line. Although absolute poverty metrics have gradually declined, a recent spike – from 34.2% in 2022 to 39.4% of the population in 2023 (World Bank, 2023) – presents significant concerns. This increase highlights the prevalence of low-income households in the nation, exemplifying the urgent need for comprehensive social protection measures. Although the IMF’s interventions in Pakistan span nearly the age of the nation itself, with the first agreement signed in 1950, social protection policies bear a contemporary shade through the IMF-backed Benazir Income Support Program (BISP) of 2003 – the sole social protection measure operating in the nation as of today. The BISP, a cornerstone of the IMF’s Quantitative Approach, provides cash transfers to qualifying low-income households with the aim of alleviating budget constraints and encouraging consumption for short- and long-term development.

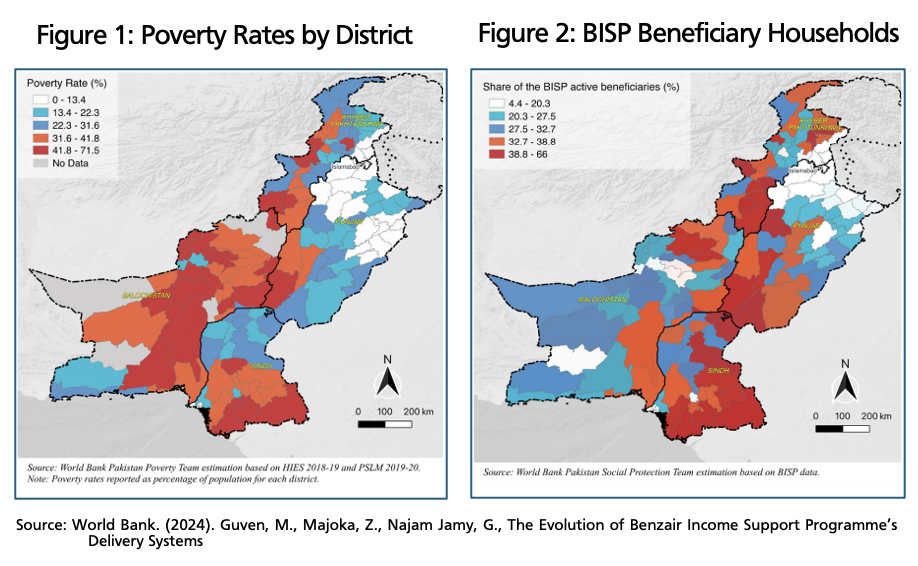

However, the IMF-backed BISP’s reliance on QA measures, such as spending targets and budgetary expenditures, raises questions about its effectiveness in reducing multidimensional poverty. For instance, a mere 4% increase in BISP expenditures at the end of 2006 was heralded as an effective policy intervention (Gazdar, 2011). Yet, this numerical increase did little to address the underlying structural issues relating to cash transfer distribution mechanisms, highlighting the pitfalls of QA developmental policies. Moreover, Figures 1 and 2 reveal a clear misalignment between poverty rates and the distribution of BISP beneficiary households across Pakistan. While some of the poorest districts (such as those in Balochistan and southern Punjab) receive lower BISP coverage, other less impoverished regions benefit disproportionately. This discrepancy raises concerns about concentrating funds in a limited number of targeted households rather than expanding the safety net to reflect actual poverty distribution. Although IMF-backed cash transfer programs provide short-term relief by helping households afford basic necessities like food and shelter, they fail to establish a long-term framework for economic inclusion and sustainable development.

Assessing the Impact: Education and Asset Retention

In a 2024 report, the IMF refers to an increase in cash expenditures by 30% from the previous year towards the BISP in Pakistan (IMF, 2024). The IMF claims that this represents an effective policy intervention by addressing two critical aims of QA policy measures such as the BISP cash-transfer:

- Investment in Education

The IMF report claims that “a direct cash transfer will alleviate the economic constraints to the access of health and education services” (IMF, 2024). However, in many rural areas, financial assistance alone does not guarantee educational participation. Many of the households targeted by the BISP lack access to adequate schools, making the cash transfer an incomplete solution to educational inequality. While the IMF emphasizes access as its primary goal, a more nuanced understanding of rural demographics reveals that infrastructure shortages prevent real improvements in educational attainment. Educational investments inherently reflect a supply-side, long-term approach to development, which can only be effective if an assessment of the initial conditions in targeted towns and neighborhoods is undertaken. While data may suggest positive action by the IMF in increasing the number of cash recipients, a multidimensional perspective reveals that long-term educational advancement for low-income households remains unfulfilled.

- Asset Retention/Accumulation for Livelihood Strategies

The IMF argues that“beyond being used for current consumption, households will be able to save some portion of the transfer and use it for asset accumulation” (IMF, 2024). However, this assumption overlooks the harsh economic realities faced by low-income households. Cash transfers do not inherently incentivize savings or asset accumulation, since families facing immediate survival challenges prioritize essential living expenses over long-term financial planning. Studies report that 50-60% of low-income households in developing countries use cash transfers primarily for immediate consumption needs rather than savings or investment (Overseas Development Institute, 2016). Thus, while the IMF sees cash transfers as a stepping stone to economic mobility, from a multidimensional perspective, they merely serve as short-term relief without addressing the structural barriers to sustainable development.

The Case for a Multidimensional Approach

By employing a solely QA methodology, the IMF fails to capture the full spectrum of economic and social realities faced by low-income households. Crucially, it overlooks the fact that while low-income families may value education, healthcare, and economic security, they often lack the structural means to achieve these goals. To combat these challenges, a multidimensional framework such as Sen’s Capability Approach offers a vital analytic perspective. This approach emphasizes not just the resources available to households but their true capabilities and freedoms to pursue meaningful improvements in their lives.

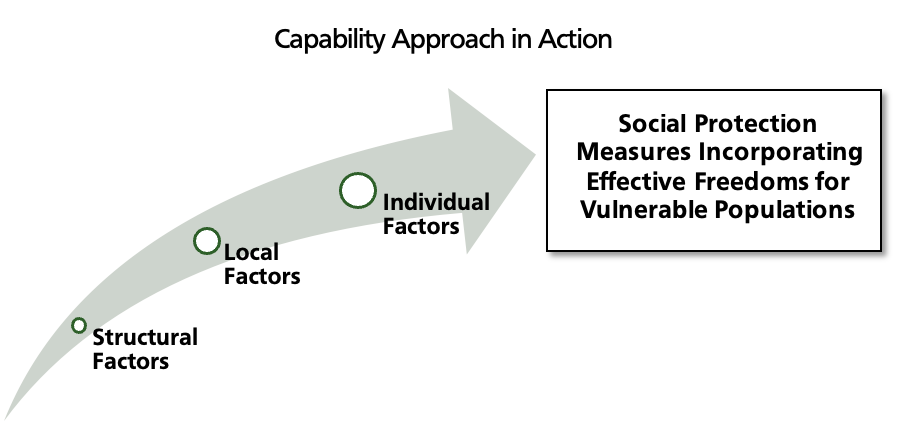

Sen establishes two foundational findings when exploring the social capabilities of individuals. First, economic prosperity is only one among many means to enrich people’s lives. Second, an increase in economic wealth does not automatically translate into greater well-being or opportunity (Sen, Development as Capability Expansion , 2003). By evoking the example of giving a bicycle to an individual without any legs, Sen argues that economic policies should be undertaken with an understanding of an individual’s capabilities. Through the CA, Sen argues that one can identify the effective and real freedoms – those concretely available to low-income households – to enable certain valued acts (Sen, Functioning and Well-Being, 1985). Applying this framework to development requires an assessment of three components: a low-income beneficiary’s individual factors, which reflect unique capacities such as physiological conditions and aspirations (e.g., an individual without legs valuing the ability to ride a bicycle); secondly, one’s local factors, which highlight the external societal circumstances that permit the achievement of valued actions (e.g., insufficient schools for families valuing education); and lastly structural factors, which relay the ways in which the political and economic environment effects people’s effective freedoms (e.g., the degree of political repression or income deterioration) (Frediani, 2010). By deducing these components for a low-income recipient of IMF funding, social protection measures can be designed in a way that places the effective freedoms of vulnerable populations at the fore.

In economic policy decisions, Sen contends that these freedoms are discerned primarily in two forms: instrumental freedom, which treats statistical increases and rising expenditures as effective economic action, and intrinsic freedom which (while increasing overall QA metrics) focuses on affirming true liberties and opportunities for vulnerable individuals, enabling them to ascend the social mobility ladder (Sen, Development as Capability Expansion , 2003). In line with this dichotomy, IMF-backed cash transfers affirm an instrumental value to development where the mere capacity for beneficiaries to utilise funding to sustain their livelihoods is equated with social protection. Yet, if developing intrinsic freedoms were the aim, the initial gains from cash transfers must be built upon by actualising freedoms within an individual’s capability space, composed of the individual, local, and structural factors. A social protection policy that neglects these crucial components cannot provide a platform to achieve long-term development. For example, the National Rural Support Program (NRSP) in Pakistan emphasises the utility of multidimensional approaches in development. By focusing on sustainable development initiatives through capacity building and income-generating activities via micro-insurance, the NRSP enhances the capabilities of low-income individuals and households in rural areas, aiming for long-term socioeconomic development rather than the BISP’s focus on short-term budget relief (Frölich, Landmann, Midkiff, & Breda, 2014). For more effective social protection, policies such as the NRSP should be encouraged by IFIs such as the IMF, as opposed to policies which tend to constrain long-term development of low-income beneficiaries.

Conclusion: Rethinking IMF Development Strategies

The IMF possesses an unrivalled ability to champion a truly multidimensional approach to development, but it must move beyond its exclusive reliance on quantitative metrics. By embracing frameworks such as the Capability Approach, the IMF can design policies that account for the real freedoms and constraints faced by vulnerable populations via contingent funding and context-dependent policy measures. Though the socioeconomic challenges in emerging economies present a complex web of mismanagement, this further underscores the need for global IFIs such as the IMF to lead the enterprise of holistic policymaking. Instead of measuring success solely through financial disbursements, the IMF must adopt a model that actively fosters social mobility, enhances local capacity, and prevents long-term dependency. Whether it be South Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, or Latin America, the effectiveness of social protection policies depends on their ability to enable true economic freedom, not just temporary relief. Only then can the IMF fulfil its mission of creating an equitable and sustainable global economy – one that fosters the potential for transformative change across the developing world.

Works Cited

Cheema, I., Hunt, S., Javeed, S., Lone, T., & O’Leary, S. (2016). Benazir Income Support Programme: Final Impact Evaluation Report. Oxford Policy Management .

Frölich, M., Landmann, A., Midkiff, H., & Breda, V. (2014). Microinsurance and Child Labour: An impact evaluation of NRSP’s (Pakistan) microinsurance innovation . International Labour Organisation.

Frediani, A. A. (2010). Sen’s Capability Approach as a framework to the practice of development. Development in Practice , 173-187.

Gazdar, H. (2011). Social Protection in Pakistan: In the Midst of a Paradigm Shift? Economic and Political Weekly, 59-66.

IMF. (2017). IEO Evaluation Report: The IMF and Social Protection.

IMF. (2024). IMF Pakistan Report: First Review Under the Stand-By Arrangement . IMF.

Lagarde, C. (2012). Back to Rio—The Road to a Sustainable Economic Future. IMF.

Oversees Development Institute. (2016). Cash transfers: what does the evidence say?

Sen, A. (1985). Functioning and Well-Being. In A. Sen, Commodities and Capabilities (pp. 17-22).

Sen, A. (2003). Development as Capability Expansion . In Sakiko Fukuda-Parr, Readings in human development : concepts, measures and policies for a development paradigm (pp. 41-58).

World Bank. (2023). Poverty & Equity Brief: Pakistan October 2023.

World Bank. (2024). Guven, M., Majoka, Z., Najam Jamy, G., The Evolution of Benzair Income Support Programme’s Delivery Systems