It is widely accepted that the fundamental economic problem – the distribution of finite resources across infinite human wants/needs – is the cornerstone of the economics discipline. This focus is accompanied by the idea that economic growth is the ultimate objective to remedy this dilemma. Yet, covert within these assumptions lies an inherent contradiction: how can nations and corporations chase endless growth when any given state’s resources are, by definition, finite? Economic discourse is rife with the use of the GDP (or GDP per capita) metric, which remains the dominant gauge for economic success, shaping policy decisions and public understanding. However, this paradigm warrants a deeper evaluation. In an age of widespread inequalities and environmental decay, GDP-centric growth no longer serves as an effective economic objective. Instead, by focusing on human/environmental costs and the implications of stagnation, there exists an urgent need to redefine economic success.

The Grand Deception of GDP and Wealth

GDP and GDP per capita dominate as proxies for economic well-being, yet Nolan et al (2016) reveal a critical flaw in this assumption: despite rising GDP, household incomes for ordinary citizens have failed to follow suit. As illustrated in the figure, in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, GDP per capita climbed while median household income steadily declined, illustrating a clear divide between macroeconomic indicators and true household well-being. This divergence highlights a troubling reality – economic figures often cited by the media and politicians can obscure the lived experiences of households, particularly when prosperity remains elusive despite economic growth.

This stark economic disparity is similarly highlighted by Hazell and Holmes (2021), citing a $36,000 gap between GDP per capita and median income in the US in 2018. This disparity has likely been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic by disproportionately affecting low-income households, with research already predicting that ‘the pandemic is likely to widen income inequality over the long run’ (Meyer et al, 2024). As a result, as opposed to adopting policies that address widening income inequality, governments eager to project economic recovery will prioritise GDP growth, opting for headline figures rather than tangible improvements in citizen well-being.

At home, the UK’s Labour government has declared economic growth its “number one mission”, aiming to achieve the highest GDP growth in the G7 (Gov.uk, 2024). However, this singular focus on GDP raises serious concerns about the distributional effects and the long-term sustainability of the objective. In 2022, “incomes for the poorest 14 million people fell by 7.5%, whilst incomes for the richest fifth saw a 7.8% increase”’(Equality Trust, 2023), despite GDP per capita (adjusted for PPP) remaining relatively unchanged (World Bank, 2025). This suggests that GDP alone is failing to translate into shared prosperity. If economic growth, as advocated for by the government, continues to disproportionately benefit the wealthiest, can we truly call it progress for the UK in the long term? Can citizens expect corporate profits to trickle down and improve their well-being? This short-termism is an inherent flaw in fixed term democratic systems, where successive governments pursue lofty GDP growth figures that bolster re-election prospects, even when they fail to address deeper structural inequalities.

All of this raises a critical question: is our macroeconomic obsession with growth still a net positive in the modern era? Historically, prioritising this paradigm has helped countries industrialise, rebuild after destructive wars, and lift populations out of poverty. However, in our shifting global economy, the costs of unchecked growth extend far beyond sovereign borders. Externalities from climate change to financial instability shape economic realities, making it imperative to reconsider how growth effects the whole world, not just domestic nations.

Growing Pains – How Global Growth Exploits People and Planet

A commonly cited advantage of globalisation is increased efficiency and cost-cutting. In search of profit maximisation, transnational corporations seek the most competitive deals on labour, raw materials and capital. This practice is often framed as a win-win, benefiting both trans-national corporations (TNCs) and host countries. However, this narrative obscures the exploitative practices that underpin the majority of global trade.

In practice, however, the so-called efficiency gains of outsourcing production to developing countries are the product of weak labour protections rather than genuine economic benefits. Muchlinksi and Arnold (2024) point out that TNCs regularly disregard local labour laws and engage in exploitative practices. More alarmingly, they rely on forced labour and various forms of modern slavery (Singh and Mishra, 2024). Some argue that lower labour standards and lax regulations are necessary trade-offs for developing countries to grow and catch up. However, empirical evidence contradicts this claim – high labour standards are, in fact, strongly correlated with long-term economic development (Langille, 2009).

A similar flawed logic underpins the extraction of natural resources. Traditional economic theory suggests that countries with large raw material endowments can utilise these resources by selling to the global market. However, empirical observations from a resource-rich region like Africa contradict this assumption: not only has widespread resource exploitation failed to promote sustained growth or industrialisation (Nkemga et al, 2021), it has engendered exploitative “informal employment” practices (Danquah et al, 2023). This phenomenon aligns with what economists have termed the “resource curse”, where resource wealth paradoxically stunts industrialisation and economic diversification. Some authors link this persistent economic stagnation to neocolonial extraction methods, which benefit foreign actors at the expense of local development.

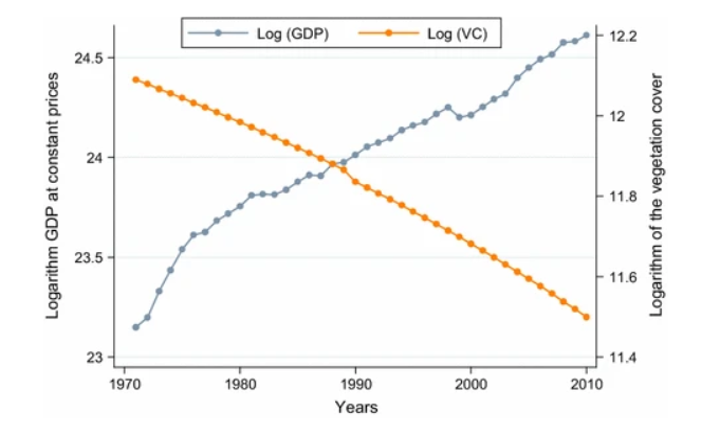

Beyond labour and resource extraction, the ‘literature has almost concluded that economic activities and growth contribute significantly to environmental degradation’ (Acheampong and Opoku, 2023). Evidence overwhelmingly demonstrates that a reduction in consumption and production by wealthy nations is necessary to tackle ‘climate change, biodiversity collapse, ocean acidification, water scarcity and other environmental problems’ (Paulson, 2022). Given the accelerating climate crisis, scientific consensus increasingly calls for a reduction in unchecked economic growth which is driving environmental degradation.

The neoliberal promise that international trade – in tandem with economic growth – leads to mutually beneficial gains doesn’t hold under scrutiny. Beneath the surface of profit-driven expansion lies a foundation of labour exploitation, resource extraction and environmental destruction. While GDP figures may signal growth, the quality of this growth – namely, the impact on human lives and our ecosystem – remains brazenly overlooked. Individuals committed to traditional market analysis might argue that growth and prosperity are intertwined, and that stagnation is a death sentence for economic well-being. However, by examining this claim through the following case study, the assumption that infinite growth is desirable becomes increasingly baseless.

Stagnation and Potential: Lessons from Japan

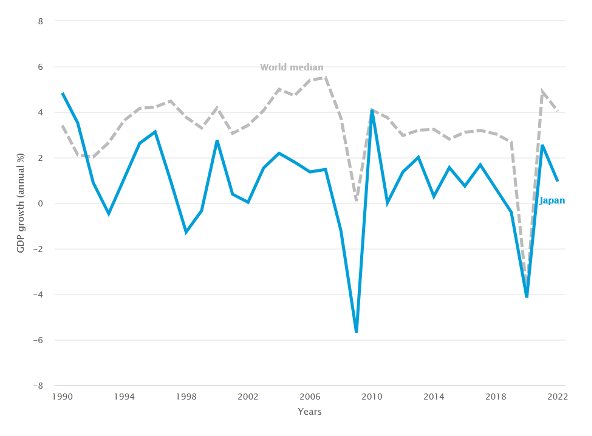

The UK’s stagnant economy has been a focal point of concern since the financial crisis, with low productivity often blamed for the country’s sluggish growth (Ridpath, 2024). Successive governments have sought to buck this trend, operating under the assumption that a stagnant economy equates to economic decline. How true is this assumption in practice? Japan, a country that has experienced three decades of near-zero GDP growth, provides an illuminating case study.

Once an economic powerhouse poised to rival the US, Japan has remained stagnant for over 30 years (Hayashi, 2023). Yet, despite this stagnation, Japan ranks among the highest in life expectancy, education quality, employment security, and environmental sustainability (World Bank, 2023). Moreover, Japan is perhaps the only large economy major economy not facing a housing crisis, offering affordable home ownership to a greater share of its population. This means that a citizen born in Japan can on average expect a longer, healthier, and more educated life, in conjunction with home ownership and job security. Though Japan faces domestic issues ranging from an ageing population to a low English language proficiency hindering access to global business, it is certainly an outlier in the global economy. As Nobel-prize winning economist Simon Kuznets noted, there are four types of economies: “developed, developing, Argentina and Japan”. This distinction reflects how Japan, despite stagnation, has resisted the economic pitfalls often associated with slow growth, defying conventional expectations.

For many, the question may arise as to how it is possible that despite years of stagnation, Japanese citizens enjoy some of the highest standards of living in the world. Yet, instead of questioning why this has been the case, perhaps the more important query is why it should grow at infinite rates at all if it already has a stable and prosperous economy. As Kuznets contends, there are countries that waste their potential (such as Argentina), and countries that achieve their full potential (such as Japan). Since economics is focused on the initial problem of distributing finite resources efficiently, it’s not unreasonable to suggest that Japan is resolving this dilemma from a heterodox standpoint.

Japan’s case serves as further evidence that chasing GDP growth at all costs is not only unnecessary but often detrimental to societal well-being and environmental stability. While it would be naive to abandon growth as an economic target entirely, Japan’s experience suggests that well-being, sustainability, and income distribution may serve as more meaningful indicators of economic success than GDP alone. In line with this, by virtue of the lack of faith in GDP metrics, an alternative metric such as the Human Development Index (HDI) must be explored.

HDI: An Alternative Gauge for Economic Success?

Developed by the UN Development Program, HDI is a metric which provides a more holistic understanding of economic well-being, incorporating health (life expectancy), living standards (GNI per capita) and education (mean years of schooling). Unlike GDP, HDI prioritises human welfare, offering a clearer picture of how a nation’s citizens are actually faring.. The contrast between GDP and HDI rankings is striking. The US, despite leading in GDP, falls behind countries like Singapore, Norway, Canada, Germany, and Japan in HDI rankings. This suggests that high economic output does not automatically translate into better living standards and well-being.

If international institutions and policymakers prioritized metrics such as the HDI over GDP, developing countries would be incentivised to strengthen healthcare and education systems rather than adopting policies that attract foreign direct investment at the expense of labor rights. Likewise, in the UK, an HDI-centric approach could encourage policies that address regional and income inequalities as well as expanding opportunities for more talented and intelligent citizens to get involved in innovation and research. HDI isn’t a perfect measure of wellbeing – it relies on broad averages and doesn’t capture governance or wealth distribution -yet it offers a far more comprehensive measure of human progress than GDP alone, making them a stronger foundation for policies that prioritise both people and planet. The key takeaway is that output as a goal implicitly administers a culture of consumerism, which has negative ramifications for both people and planet.

Obstacles in the Way – A World Unready

Challenging growth as the ultimate economic objective may seem radical, yet a growing body of literature suggests that hyper fixation on GDP enables exploitation, deepens inequity and accelerates environmental degradation. Transitioning away from GDP-centric policymaking is both desirable and necessary, but deeply held interests stand in the way. Governments fear that stagnant economic growth will weaken re-election prospects, and trans-national corporations – whose profits are tied to perpetual growth – are likely to resist systemic changes that hinder their bottom line.

Yet, history has repeatedly shown that economic paradigms evolve. Feudalism gave way to mercantilism, which evolved into classical economics, then Keynesianism, and eventually neoliberalism. Each shift was considered radical in its day, yet each became the dominant ideology. As global challenges intensify, a new transformation should focus on the planet and its people. The global economy has the potential to meet the needs of the world without compromising its future – will we embrace this transformation or stand in our own way with a mode of thinking predicated on perpetual growth?

References

Acheampong, A. O., & Opoku, E. E. O. (2023). Environmental degradation and economic growth: Investigating linkages and potential pathways. Energy Economics, 123(106734). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2023.106734

Danquah, M., Osei-Owusu , A. K., & Towa, E. (2023, June 14). UNU-WIDER : Blog : Rethinking African debt and exploitation of natural resources. Www.wider.unu.edu. https://www.wider.unu.edu/publication/rethinking-african-debt-and-exploitation-natural-resources

Equality Trust. (2023). The Scale of Economic Inequality in the UK. Equality Trust. https://equalitytrust.org.uk/scale-economic-inequality-uk/

Government, H. (2024, December 5). Kickstarting Economic Growth. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/missions/economic-growth?

Hayashi, F. (2023). The Root Cause of Japan’s 30-year Stagnation: Implications for the U.S., Europe, and East Asia. Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4553699

Hazell, J., & Holmes, D. (2021). Measuring global inequality: Median income, GDP per capita, and the Gini Index. Givingwhatwecan.org; Giving What We Can. https://www.givingwhatwecan.org/blog/measuring-global-inequality-median-income-gdp-per-capita-and-the-gini-index#final-thoughts

Langille, B. A. (2009). What is International Labor Law For? Law & Ethics of Human Rights, 3(1), 48–82. https://doi.org/10.2202/1938-2545.1030

Meyer, P. B., Piacentini, J., Frazis, H., Schultz, M., & Sveikauskas, L. (2024). The Effect of the Covid‐19 Pandemic on Inequality. Review of Income and Wealth, 71(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12707

Nolan, B., Roser, M., & Thewissen, S. (2016). GDP Per Capita Versus Median Household Income: What Gives Rise to the Divergence Over Time and how does this Vary Across OECD Countries? Review of Income and Wealth. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12362

Paulson, S. (2022, September 13). Economic growth will continue to provoke climate change. Impact.economist.com. https://impact.economist.com/sustainability/circular-economies/economic-growth-will-continue-to-provoke-climate-change

Ridpath, N. (2024, October 29). Why isn’t Britain getting richer anymore? | Institute for Fiscal Studies. Institute for Fiscal Studies. https://ifs.org.uk/articles/why-isnt-britain-getting-richer-anymore-0

Singh, A., & Mishra, A. (2024). Forced Labour, Global Supply Chain and TNCs: Recent Trends and Practices. Global Trade and Customs Journal, 19(10). https://kluwerlawonline.com/journalarticle/Global+Trade+and+Customs+Journal/19.15/GTCJ2024073

United Nations. (2022). Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index. Hdr.undp.org. https://hdr.undp.org/inequality-adjusted-human-development-index#/indicies/IHDI

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2024). Human Development Index. United Nations Development Programme; United Nations. https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/human-development-index#/indicies/HDI

World Bank. (2023). Japan | Data. Worldbank.org. https://data.worldbank.org/country/japan

World Bank. (2025). GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) – United Kingdom | Data. Data.worldbank.org. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD?locations=GB