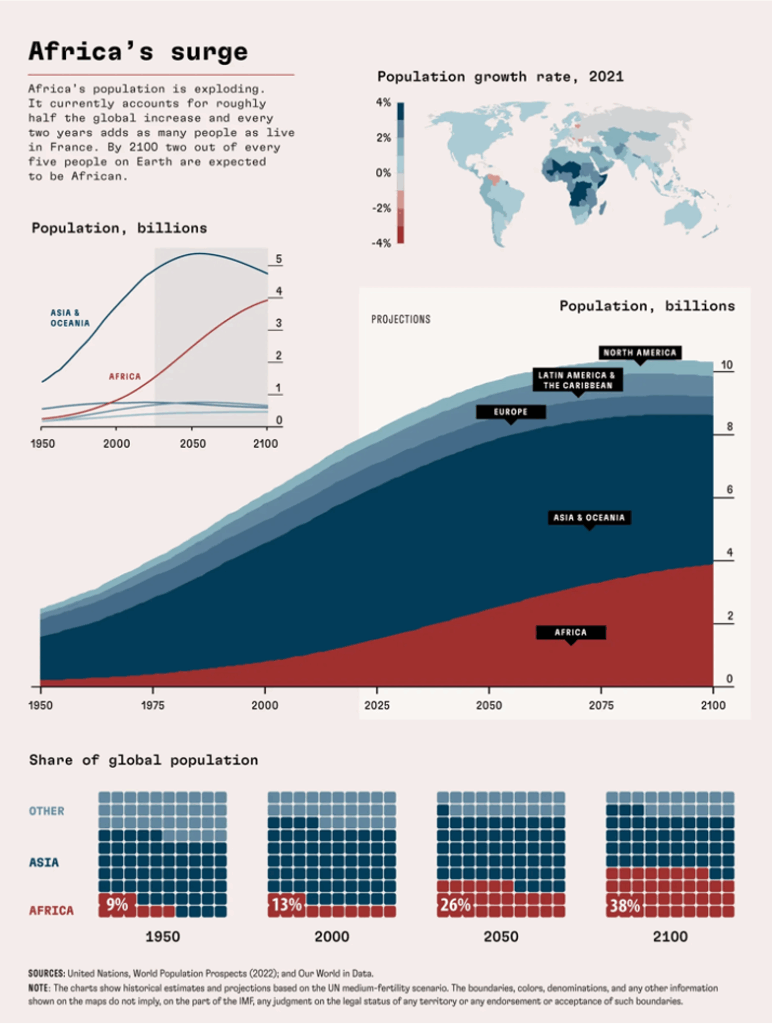

For centuries, Africa has been at the heart of the global economy – yet rarely on autonomous terms. Endowed with rich natural resources as well as human potential, the continent has long been shaped by external powers that dictate its economic trajectory. Today, despite political independence in many African nations, Africa remains constrained to structures within the global economy. Meanwhile, rising political extremism, trade isolationism, and protectionist stances across the world threaten to exacerbate dire circumstances in Africa (Khan, 2024), leaving nations vulnerable to worsening crises such as mass displacement, climate degradation and persistent conflict.

As Dr. Mark Langan highlights, understanding African insecurity must explore how external actors have enabled insecurity in the preservation of their lucrative economic arrangements within Africa (Langan, 2017). This is similarly relayed by sub-altern thinkers such as Tarak Barkawi where he states that exploitative financial and institutional tools have perpetuated and maintained the continued imbalance between the “Global North and South” (Barkawi, 2006). The desire to subvert these politico-economic impositions found resonance in Pan-Africanism – a movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between the communities of Africa. Africa should not remain passive in this transformational shift of the global economy. Historically African liberation movements for continental unity have sought to challenge the imposition of external constraints and unveil the exploitative tendencies they engender. Kwame Nkrumah, the former president of Ghana and a leading figure of Pan-Africanism stated that neo-colonialism is the worst form of imperialism, for those who enforce it accept power without responsibility and for those who suffer under it face exploitation without recompense (Nkrumah, 1965). Though these imperialist efforts were unable to dismantle Africa’s structural dependencies in the global economy, they provide countless lessons to guide the contemporary age. The rise of multipolarity, BRICS, and China’s involvement in the continent pose renewed dilemmas – will Africa be able to foster its own agency, or will dependency remain dominant?

To explore these questions, the impetus of Pan-Africanism and the extent to which it is able to challenge these systemic dependencies must be assessed. Further, the possibility for economic unification through currency cooperation, and the role of natural resource sovereignty must be re-examined.

Pan-Africanism: Aspirations and Challenges

Nkrumah envisioned a Pan-African state as one in which all Africans would be united through shared historical and geographical bonds, transcending ethnic and cultural diversities. (Nkrumah, 1965) He saw Pan-Africanism not just as an ideological aspiration but a strategic necessity – a means of consolidating Africa’s resources and strengthening its economic independence. The ideology evolved significantly over the course of the 20th century, finding prominence during the black liberation movement of the 1950s and 60s in Africa and the West. (Onimisi, 2023). In the early post-independence era, leaders such as Nkrumah, Julius Nyerere, and Sekou Touré sought to institutionalize Pan-African unity through the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), established in 1963. The OAU aimed to promote continental solidarity and accelerate the decolonisation process, envisioning that a politically and economically unified Africa could collectively resist external dominance.

However, despite the symbolic significance of this organisation, it lacked enforcement mechanisms required to drive meaningful economic and political integration (Mkandawire, 1999). With the rise of African sovereign states in the 1960s, nationalist priorities began to take precedence over solidarity, and a desire to ascertain national self-interest took hold. This shift fragmented the momentum of Pan-Africanism, reinforcing a recurring theme of constrained potential. Though this situates the historical relevance of Pan-Africanism, contemporary dynamics affirm this fragmentation: a recent dismissal of African nations’ bid for a permanent seat on the UN security council serves as a stark reminder of the continent’s continued marginalization in global governance. Developments such as these emphasize the need to rethink Pan-Africanism’s role in the 21st century.

For African nations to maximise their potential, a new ideology must contend with the differing identities, interests and concerns of diverse nations. It must also ascertain some form of authority and control over the continent (Mkwandawire, 2004). Yet, rather than pursuing this through the historically fraught path of military alliances, a more pragmatic alternative lies in the prospect of economic integration – specifically, the pursuit of shared monetary objectives and a common currency. Not only would this avoid exacerbating existing tensions, but a continental economic framework would offer a more strategic and unifying solution to the woes of African nations.

The Merits of a Unified Economic System

Economic unification in Africa has the potential to overcome socio-political barriers that underpin Pan-Africanism. A strong, integrated African economy could serve as the foundation for broader political solidarity, reducing foreign exploitation and positioning the continent as a major force in the global economy. On the surface, this may seem like a radical step, yet economic cooperation across geographies has been the hallmark of greater multilateralism – the EU’s monetary union relays the possibility for such an endeavor. But a critical first step would be to empower the African Central Bank (ACB) as the governing body responsible for monetary policy and financial oversight across the continent. As the African Union relays, this would require close collaboration with national central banks within the continent so that a continental economic strategy and domestic fiscal autonomy remains balanced (African Union, 2013). In similar fashion to the EU, an effective ACB would require an overarching political hub tasked to guide and act in the interest of the continent. By utilising the economic dictates of the monetary union, this political solidarity would “coherently” address issues of both state and non-state import on a more expansive scale to that of the EU (Murobe 2000:58). As a result, regional economic hubs – North, East, South and West – would be established as adept intermediaries on policies and trade harmonisation.

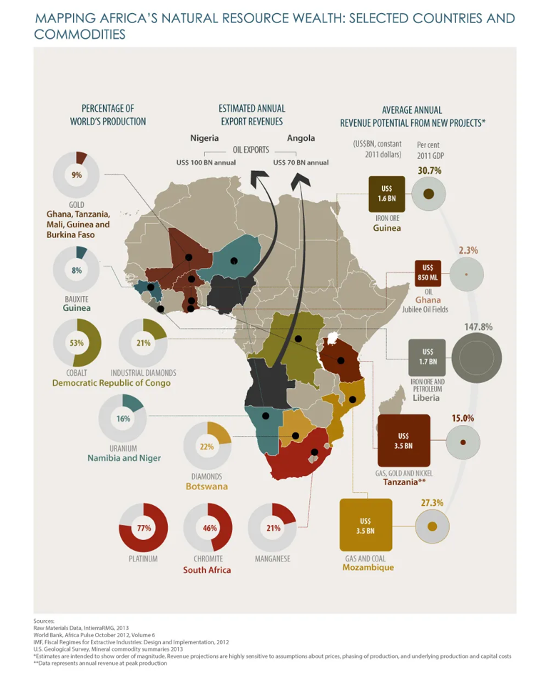

Crucially, however, with any far-reaching economic unification, there is the question of governance and regulation. A Pan-African economic system must determine the extent of market intervention, trade protectionism, and foreign investment controls to prevent economic exploitation. According to the UNEP, Africa is home to 30% of the world’s mineral reserves, 8% of its natural gas, 12% of oil reserves, 40% of gold reserves, and houses the largest reserves of cobalt, diamonds, platinum and uranium (UNEP, 2025).

Yet, Africa loses an estimated $195 billion USD annually through illicit financial flows and weak regulatory structures (UNEP, 2025). A unified economic system, under the authority of the ACB, could redefine Africa’s approach to resource management by negotiating fairer deals and creating grater local value before commodities reach global markets. In light of growing labour and income disparities, a strong ACB could pave the way for meaningful changes in labour market standards across the continent.

The Imperial Resource Curse: Examining the Democratic Republic of Congo

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) exemplifies the devastating consequences of foreign interference, resource exploitation and economic mismanagement. During its occupation of the Congo, the Belgian crown imposed a system of racial hierarchy amongst the 250 local ethnicities, critically favoring the “Tutsi” ethnic group. The Belgians left the region with a deeply ingrained system of ethnic stratification, entrenching a constant state of insecurity and heightening militarism which plagues the nation to this day. In the contemporary era, this legacy of exploitation has been compounded by multinational corporations and global powers vying for control over the DRC’s vast mineral wealth. The country holds over 60% of the world’s cobalt reserves, a crucial component in lithium-ion batteries used in electric vehicles and consumer electronics. This resource wealth has fueled a new wave of neocolonial extraction, with companies from the U.S., China, and Europe deeply involved in mining operations, often in ways that perpetuate economic instability and social conflict. The UNHCR states that “very little revenue from natural resource exploitation has been used to contribute to the countries overall development or raise its people living standards.” (UNHCR, 2003).

The country’s dire economic conditions are further reflected in its ranking of 179th on the Human Development Index (HDI) (World Bank, 2024). Beyond economic stagnation, foreign interests have intensified social and humanitarian crises. Amnesty International has extensively documented the devastating effects of resource extraction by TNCs in the DRC (Callamard, 2023).

A glaring example occurred in February 2020, when reports from the Kolwezi region detailed forced evictions and violence carried out by government troops acting on the behalf of a subsidiary of Eurasian Resources Group (ERG), a Luxembourg-based TNC. (Amnesty, 2023). Crucially, however, the case of the DRC is not in isolation – they are symptomatic of a broader pattern of displacement and instability. The bloodshed and instability fuelled by resource wars are not unique to Congo; they are reflective of a continental crisis in which Africa’s vast natural wealth remains a source of external exploitation rather than domestic prosperity (Al Jazeera, 2025). In the eastern city of Goma for instance, as part of an ongoing 30-year ethnic conflict, M23 Rwandan backed rebels lay siege against a corrupt and underfunded Congolese army, displacing thousands and entrapping millions (Al-Jazeera, 2025).

In this environment, Pan-African unity is not just an ideological aspiration but an urgent necessity – without a collective politico-economic strategy to control and regulate Africa’s wealth, the continent cannot escape the viscous effects of foreign dependence and internal conflict.

From Exploited to Empowered: Africa’ s Politico-Economic Future

It is no secret that the world’s economic and technological infrastructure is deeply dependent on Africa. Without its vast reserves of critical minerals, energy, and agricultural outputs, global production and innovation would face severe disruptions. Yet, despite its indispensable position in global supply chains, Africa continues to fragment economically and engage in forms of dependency with external actors. A united economic Africa could reverse this imbalance, leveraging comparative advantage by strategically optimising its environmental, industrial and infrastructural strengths. By examining cross-regional potentialities, a unified economic system could invest in high-potential sectors, establishing a more self-sustaining and globally competitive economic model (Onimisi, 2023: 1). Moreover, by benefitting from these economic gains, African unification could serve as a geopolitical force in an increasingly multipolar world order.

The rise of an economically consolidated African bloc, embodying the prospects of a historically repressed and marginalised continent reclaiming its rightful sovereignty, stands as a monumental case for the possibility of economic justice on a global scale. While the challenges of attaining this Pan-African feat are significant, the stability it could bring to the continent firmly eclipse the risks. Ultimately, if Africa’s resources have powered the world for centuries, then perhaps it is time for them to power Africa itself.

Works Cited

African Union. (2013). Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want. African Union Commission. https://au.int/en/agenda2063

Al Jazeera. (2025). Conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo: The role of M23 rebels and resource exploitation. Al Jazeera.

Al Jazeera. (2023). Rare access inside one of the world’s longest running conflicts. Witness Documentary.

Amnesty International. (2023). DRC: Cobalt and copper mining for batteries leading to human rights abuses. Amnesty International.

Barkawi, T. (2006). The postcolonial moment in security studies. Review of International Studies, 32(2), 157-177.

Callamard, A. (2023). Resource exploitation and human rights violations in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Amnesty International.

Khan, S. (2024). Declining Democratic Resilience: The New Extremism Landscape. Crest Advisory.

Langan, M. (2017). Let’s talk about neo-colonialism in Africa.

Mkandawire, T. (1999). Shifting commitments and national cohesion in African countries. UN Research Institute for Social Development.

Mkandawire, T. (2004). Social Policy in a Development Context. Palgrave Macmillan.

Murobe, M. (2000). The Political Economy of African Integration: Challenges and Prospects. African Journal of Political Science, 5(1), 58-75.

Nkrumah, K. (1965). Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism. Thomas Nelson & Sons.

Onimisi, P. D. (2023). Leveraging Africa’s Comparative Advantage for its Development in a Globalised World. African Economic Research Consortium.

UNEP. (2025). Africa’s Resource Wealth: The Impact of Exploitation and Financial Flows. United Nations Environment Programme.

UNHCR. (2003). Natural Resource Exploitation and Its Impact on the DRC’s Development. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

World Bank. (2024). Democratic Republic of Congo Overview: Economic Indicators and HDI Ranking. World Bank.